Keine Ferne macht dich schwierig,

Kommst geflogen und gebannt

No distance makes you difficult,

You come flying, and stay under a spell

—Goethe

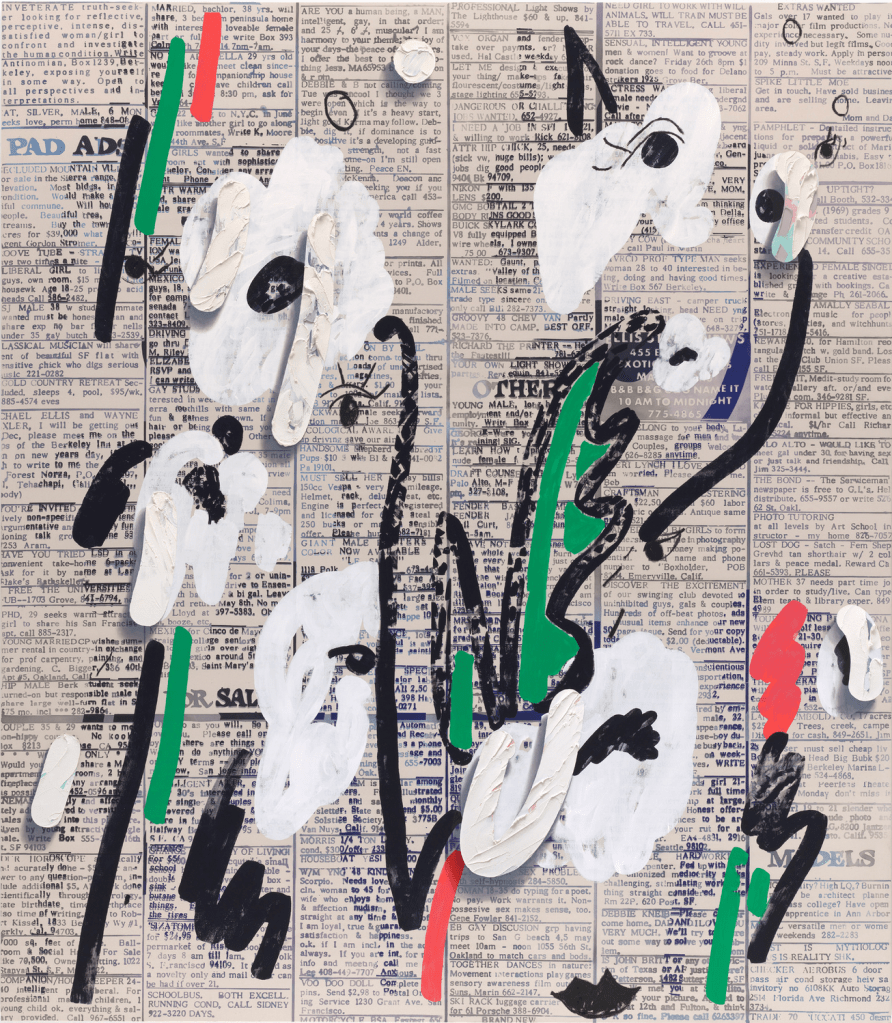

Laura Owens, Untitled, 2013

Years ago, when I was teaching myself about art, I came across a curious exhibit at the MoMA: The Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World. This exhibit gathered work by 21st century painters, including Laura Owens and Julie Mehretu. Its organizing principle, I thought, was that all the artists collected had extricated themselves from history—from a tradition that one either aligns with or disavows. Hence the exhibit’s title. These artists were contemporaneous with all art epochs, thus with none.

That exhibit seemed particularly radical to me as I had just read The Story of Art by E.H. Gombrich. Like Hegel, Gombrich charts the development of Western art, and discerns a logic that underlies this tradition, out of which one can shape a narrative. The Story of Art sums up, for a popular audience, the “temporality” that that exhibit’s artists were free from.

One way to track the evolution of a tradition is to follow its depiction of space. Gombrich saw “a continuous effort” throughout Western art creation, one that was set in motion in Ancient Egypt, where artisans composed hieroglyphs and paintings out of multiple perspectives of objects, usually arranged paratactically.

Tomb of Nebamun (Thebes) circa 1350BC

Much later, as we know, optical laws were elaborated in the Renaissance so as to capture retinal reality on canvas, fixing receding objects in one angle. Forced perspective became for centuries afterwards an iron law of pictorial space. Even Surrealists like Yves Tanguy, who had little fidelity to reality, made use of it. At the tail end of Gombrich’s “story,” Abstract Expressionists diluted perspective’s supremacy, much as they violated other orthodoxies.

Yves Tanguy, Indefinite Visibility 1942

What I found compelling about the Forever Now exhibit was that these artists worked in a context where the historical development of perspective had already been sublated. Perspective was a problem that had been worked through in the past two centuries; now, it could be tidily sloughed off. The Forever Now’s artists seemed to me “atemporal,” perhaps even acultural, in their very indifference to what was once a rule of imaginative space. Through that indifference, they intimated what was possible, once liberated from the retina.

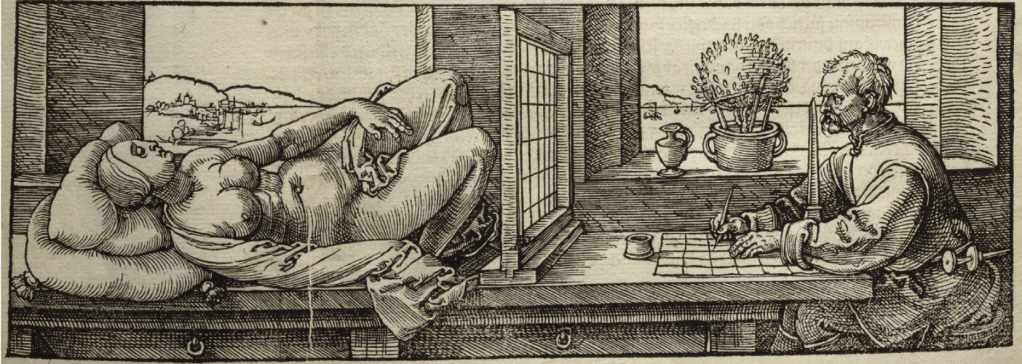

Albrecht Dürer, from Treatise on Measurement 1525

Perspectivism is still taken for granted in the West. Despite the Abstract Expressionists, it’s not an easy thing to void.

You might remember how grade school students are taught to draw pictures. First draw the horizon—a line, in infinity, where the sky meets the earth. Then, to create the illusion of depth, arrange forms such a way that continually diminish in size as they approach that horizon. Later, one learns about rules of optical convergence, thereby sharpening the illusion.

Despite its apparent intuitiveness, this approach to draftsmanship was found almost nowhere in the world before Renaissance Italy, at least according to art historian Samuel Edgerton, who wrote a notable book on the subject. It’s a learned practice, Edgerton notes, like reading or writing. And yet Westerners believe it to be a cornerstone of visual art as such.

The development of forced perspective was not undertaken out of respect for verisimilitude. Nor for the frisson of trompe-l’œil. It began, in the Trecento, as a spiritual exercise.

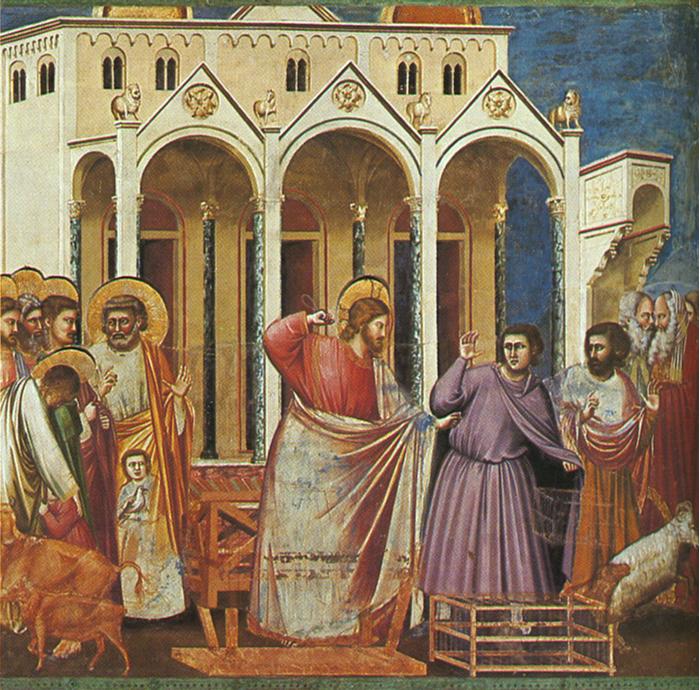

Giotto di Bondone, a Florentine painter, was likely the first to extract Jesus, Madonna, and saints from the utopian background in which they were then situated: an undifferentiable field of gold. By instead encasing those personas in a real setting—fixing them in one perspective—Giotto made their presence immanent on earth. Their holy lineaments could be witnessed in the same way that one perceived a stone church. The divine met a viewer’s gaze, at eye level.

Giotto di Bondone, The Expulsion of the Moneylenders from the Temple c. 1305

Ritual was the substrate on which this artistic innovation grew. In Giotto’s day, scenes from the gospels and canon were performed live by the public. The city’s walls and arcades served as a kind of stage set, which transmuted Nazareth and Galilee into Florence. The earliest forays into depicting forced perspective were, essentially, rudimentary photographs of these rituals. One can view the back panels of Duccio’s Maestà altarpiece as an Instagram gallery of Jesus’s life. Moreover, the association between performance and painting was actualized: Byzantine-style eikons lent their transcendent power to (or were the focus of) this community theater.

When it entered the world, perspective appeared paranormal in a way that’s difficult to conceive of now. According to medievalist Johannes Fried, “contemporaries even imagined that they could step into these frescoes, so lifelike was the scene before them.”

After Giotto, painters labored to incorporate the vanishing point in their own frescoes. Some were driven mad by the ratiocination involved. Paolo Uccello became so obsessed with the geometric laws of sight that Vasari claims he scarcely worked on anything else. When Uccello’s wife called him to bed, he is purported to have said “What a sweet thing perspective is!” before returning to his desk and working until dawn. He became impoverished and scorned, unable to be drawn away from his experiments.

Paulo Uccello, The Hunt c. 1460-1470

Later artists chipped away at the dominance of this way of seeing. Perspective was a problem to be worked through insofar it was a limiting factor, like form or propriety, that constrained painting.

In the early 20th century, Cubists argued that perspectival space, limited as it is by Euclidean geometry, cannot stretch enough—is not supple enough—to contain the range of one’s personality. In On Cubism, a canonical manifesto, two Cubist painters sought to redefine pictorial space as “a sensitive passage between two spectators,” acknowledging that space is formed by the viewer in addition to the artist—and the mind in addition to the eye.

Cubists saw their project as a replenishing of the ideal space of painting, and they found its origins in Ingres. But according to On Cubism, it was with Cézanne that pictorial possibilities burst open. Warping space to their needs, the Cubists differed from him in degree, not in kind. After him, painting became more than a mere transposition of lines and color from one plane (the light on the retina) to another (the canvas).

Other artistic traditions have, of course, long shown the liberties unlocked by ignoring optical rules. David Hockney highlights a particularly rich example of this in a documentary about a Chinese scroll. Painted by Wang Wei in the Qing dynasty, the painting commemorates a tour undertaken by the Kangxi emperor. As Hockney unfolds the 72-foot scroll, he delights in how cities come to life when the figures that populate them need not diminish in size. The eye pans across space — and avenues, shops, and residences are seen in lively detail.

In passing, Hockney notes that the different treatments of perspective reflect each culture’s cosmological views. In the Christian West, there is one true god, one true way of seeing. In China, heaven touches earth at all points. One way of seeing is just as valid as another.

Wang Hui, The Kangxi Emperor’s Southern Inspection Tour , Scroll Seven 1691–1698

Xu Yang, The Qianlong Emperor’s Southern Inspection Tour, Scroll 4 1770

Hockney contrasts this scroll painting with a later one of the same genre, painted by Xu Yang, at the Qing’s cultural nadir. Here the arrangement of space has been infiltrated by Western notions of perspective; and that influence is blamed for sapping the life out of Chinese painting. In this later painting, the eye is stretched over an overwhelming emptiness. The space is more “accurate,” but thereby deadened.

It’s interesting, in light of his comments, to examine the role of perspective in Hockney’s own art. It would be incorrect to say that he eschews Western perspective. It’s still a postulate for him, so to speak. But he crumples space like paper, and enlivens one of his favorite subjects, the British landscape, perhaps through what he learned from scroll painting.

David Hockney, Garrowby Hill 1998

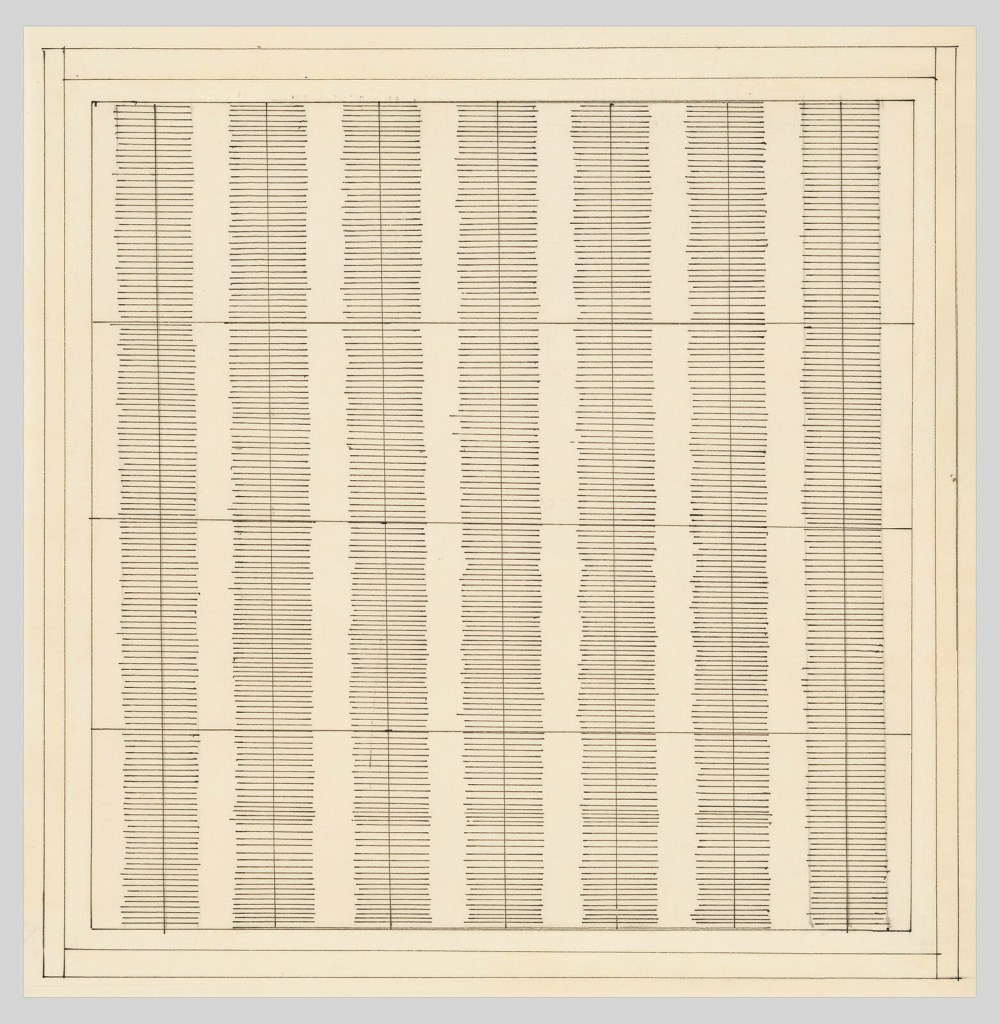

The globalization of culture is but one way that visual space has been pried open to other possibilities. Another is through the modernist insistence on the “grid.”

As Rosalind Krauss notes in a famous essay: “Unlike perspective, the grid does not map the space of a room or a landscape or a group of figures onto the surface of a painting. Indeed, if it maps anything, it maps the surface of the painting itself.”

The grid’s entrance (first in Cubism, later in Abstract Expressionism) revealed perspective to be a mere accessory to the aesthetic, whose medium is the spirit. In doing so, the modernist project sheared reality from art. The infinity intimated by perspective became contiguous with the canvas and the plane it sits on.

Agnes Martin, Untitled 1960

The digital age perhaps amplified these trends. On a computer, there is no such thing as perspective—the grid is our interface. An operating system privileges no tradition. And the perspectival lattice gives way to an infinitely mutable canvas of pixels, one that remains ethereally 2D.

I’ll venture to say we are entering a new era of the world-spirit, so far as it can be detected in its visual residue. Hegel may admit, in light of these new paintings, that art can once more take the up the fight in the elaboration of the ideal. No longer sensuous or ornamental, painting has become dialectical.

Julie Mehretu, Haka (and Riot) 2019